Adolphus A. Busch IV looked out the front door of his farm house in St. Charles County Friday morning and took in the view. Thousands of ducks of various species, snow geese and Canada geese were nestled down in the farmland and wetlands west of the Mississippi River.

As a child, he spent time on his famous beer family’s farm every August and November. He’s lived there since 1975, and inherited the farm from his father in 1985.

“I was captivated by its beauty early on,” Busch says. “This place is truly unbelievable.”

He’s talking not just about the farm, but the entire area in St. Charles County and parts of St. Louis County that sits at the confluence of the country’s two great rivers.

It’s a unique area of intrinsic beauty that also demonstrates the awesome power of water to determine its own path.

People are also reading…

Protecting that beauty, and teaching the St. Louis region about its importance, has become a quest for Busch. It was why he was one of the founders of the , a group that is going to end up in the news quite a bit over the next couple of years.

Why?

It is likely to be one of the key forces battling the next big development mistake on the horizon.

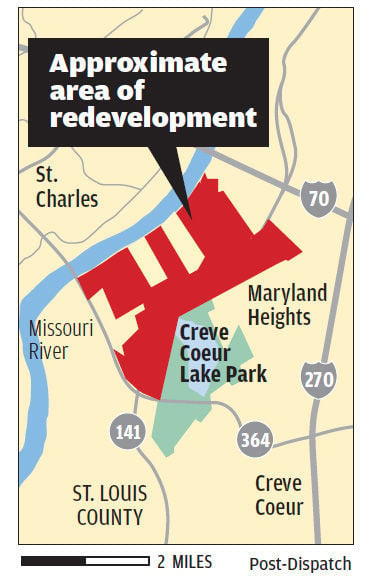

That mistake is the one announced by the city of Maryland Heights this month when it to develop 1,800 acres of flood plain along the Missouri River.

The city, and some big developers, have long sought to develop what is now mostly farmland. It’s why it invested in building the Howard Bend levee up to so-called 500-year-flood protection. That decision, of course, followed what happened in Chesterfield after the massive 1993 flood when the Monarch Levee’s reconstruction led to a massive complex of concrete and retail in what used to be the Chesterfield Bottoms. It’s why they extended Highway 141 north. The writing on the wall for this development has been there for a long time.

Busch, and many others like him, sees the Maryland Heights proposal as a debacle of Herculean dimensions. He’s serving notice that the Great Rivers Habitat Alliance, which just hired a new executive director, David Stokes, is gearing for battle.

“It’s just a disaster waiting to happen,” Busch says of the proposal to develop flood plain in an area that most certainly will flood again.

He joins a growing chorus of voices, from , to Washington University geology professor to individual homeowners who lived through the recent holiday flooding that saw waters rising faster and higher than ever before, who are urging civic leaders in the region to take a step back before putting more homes and other development in flood plain.

Criss warns that the old maps that define what is flood plain and what isn’t are no longer accurate as the combination of climate change and massive development in St. Louis, and newer and higher levees, have changed river patterns.

Indeed, Busch has a friend in St. Charles County, who recently found out that his house is now in the 100-year flood plain according to the latest Federal Emergency Management Agency maps, and it never was previously.

Put thousands of acres of concrete in the Maryland Heights flood plain, and the problems that were so prevalent in late December and early January all over the St. Louis region will be worse.

“When are we ever going to learn?” Busch asks. “How many times can we continue to make the same idiotic mistakes?”

Like Ehlmann, Busch blames the use of tax-increment financing districts as one of the worst development culprits. The tactic allows developers to earn upfront investment to reduce their risk and encourage building in areas that otherwise wouldn’t be feasible. TIF districts steal money from schools and libraries and fire districts in the meantime, without truly bringing the exponential growth promised at the outset.

Individual municipalities earn a tax windfall but the region gains nothing.

Busch is hoping that increased awareness of flood plain development in the St. Louis region, along with the connection of billionaire Stan Kroenke to the project, will create a groundswell of opposition to the Maryland Heights project. Even so, he knows approval by the City Council of whatever comes down the pike is almost inevitable. But Great Rivers Habitat Alliance is ready to fight.

It lost its last battle against a flood plain development in St. Peters, over the 370 Premier business park, but it might have won the war, as that development continues to produce little fruit.

Public awareness might be on the side of those who respect the power of America’s great rivers to forge their own path. Busch lives near that confluence and wants to save its beauty for another generation.