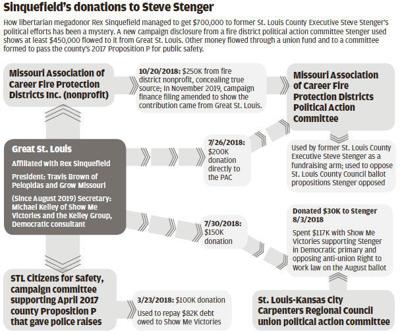

ST. LOUIS â In October 2018, a campaign committee that was helping then-County Executive Steve Stenger finance his political efforts reported a $250,000 donation from a nonprofit that supports fire districts.

But it didnât really come from the fire district nonprofit. It came from Great St. Louis, a nonprofit whose president is an operative for the St. Louis-based philanthropist and political donor Rex Sinquefield.

The true source of the donation, revealed in a November 2019 state disclosure filed by the political action committee, sheds more light on how Sinquefieldâs operation was able to funnel approximately $700,000 to Stengerâs political efforts â a sum first disclosed by federal prosecutors in August.

And it raises questions about why the disclosure was made over a year later, and whether the organizations tried to conceal Sinquefieldâs support for Stenger, who pleaded guilty in a pay-to-play scheme in May.

People are also reading…

âTheyâve given me a lot of money,â Stenger was recorded telling his executive staff in a Nov. 7, 2018, private conversation federal prosecutors included in his sentencing memorandum. âTheyâre almost up to like 700 Grand.â

How that money made its way to Stenger has been a mystery until the most recent fire district disclosure.

Sinquefieldâs organizations never donated directly to Stengerâs campaign fund.

In addition to the fire district committee, money from Great St. Louis flowed through a campaign fund for the St. Louis-Kansas City Carpenters Regional Council and into a fund that backed the countyâs April 2017 sales tax increase for police â repaying a debt held on the books for almost a year by Stengerâs political consultants.

Those donations came in 2018, first as Stenger fought for political survival in a close August primary election, and later as Sinquefieldâs operatives lined up support for the ambitious Better Together city-county merger effort. Stenger had been lukewarm to the idea when first elected county executive in 2014, and his support was crucial as the Sinquefield-funded effort prepared to reveal its plans in January 2019.

In the aborted Better Together effort, Stenger would have become the first mayor of the combined government had voters approved the proposed state constitutional amendment, drafted by attorneys at the law firm of major Stenger donor Bob Blitz. Marc Ellinger, the attorney for Great St. Louis, also used to work at that firm.

One type of political subdivision the merger would not have consolidated was fire protection districts. It would have turned the city fire department, which must compete for funding with other city departments now, into its own fire protection district with the power to levy property taxes. Area voters often support tax increases when the regionâs fire districts seek them.

The new fire district disclosure is another example of a nonprofit concealing Sinquefieldâs involvement in a political campaign. Sinquefield and Great St. Louis were revealed last month to have donated nearly $1 million to a nonprofit formed to support a failed 2018 medical marijuana ballot initiative, Missourians for Patient Care. The Missouri Ethics Commission issued a ruling Jan. 10 forcing the nonprofit to disclose its donors. Great St. Louisâ president, Travis Brown, had been a major backer of the effort, and Missourians for Patient Care hired First Rule, a division of Brownâs media firm Pelopidas, for consulting work.

The Post-Dispatch attempted to reach Sinquefield for comment but an aide deferred questions to Brown, who in an emailed response said using various committees was not an attempt to conceal Great St. Louisâ support for Stenger.

âTheyâve given me a lot of moneyâ

The first donation from Sinquefieldâs orbit that may have benefited Stengerâs political efforts appears to have been made in March 2018.

Stenger, a Democrat, was backing a sales tax increase, called Prop P, that gave St. Louis County police hefty raises â and also helped secure support from the St. Louis County Police Association for Stengerâs 2018 reelection.

Voters had approved the county sales tax increase nearly a year before, in April 2017. Sinquefield was even among the donors â many of them well-known organizations like Civic Progress and Centene â that backed the ballot initiative in early 2017; he wrote a $200,000 check as the campaign was going on.

But the campaign committee, STL Citizens for Safety, remained in operation, and it carried a debt: $82,000 owed to Michael Kelleyâs Show Me Victories, Stengerâs campaign consultants.

Great St. Louis wrote a $100,000 check to the committee in March 2018. And, soon thereafter, it paid Show Me Victories for the Prop P debt and dissolved.

Kelley, who now sits on Great St. Louisâ board, said he joined the board in August and wasnât involved in 2018 donations. Great St. Louis made a commitment to Prop P during the campaign. He doesnât know why the nonprofit took so long to send the check.

A few months later, in July 2018, Great St. Louis made another donation, this time a $150,000 contribution to the political action committee of the St. Louis-Kansas City Carpenters Regional Council, a major donor to Stenger since his first campaign for county executive in 2014.

In the days leading up to Stengerâs narrow primary victory over wealthy challenger Mark Mantovani, the carpenters union spent $117,000 with Show Me Victories on mailings that both supported Stenger and opposed the anti-union right-to-work law on the August ballot. They also gave a last-minute $30,000 check to Stenger.

A carpenters union spokeswoman said the money was used for get-out-the-vote efforts ahead of the primary, primarily against the right-to-work effort but also for Stengerâs reelection.

The fire district campaign fund

Just a few days before the donation to the union, Great St. Louis donated $200,000 directly to the fire district campaign committee. Prior to the fire district committeeâs November disclosure, that was the only contribution tying Sinquefield to Stenger. That money was used to run ads opposing county council-backed propositions giving the legislative body more power at Stengerâs expense.

Then, on Oct. 20, 2018, the fire district campaign committee reported a donation of $250,000 from its affiliated nonprofit, the Missouri Association of Career Fire Protection Districts. The maneuver shielded the true source of the donation. In all of 2017, the fire district nonprofit took in just $137,000 in revenue, according to federal tax filings.

The donation funded part of a $500,000 campaign opposing Amendment B on the November 2018 ballot, a measure that gave the St. Louis County Council â at war with Stenger â more authority to appropriate money without Stengerâs approval.

That fire district nonprofitâs former president, Dave Tilley, was Stengerâs fundraiser and is currently chairman of Central County Fire and Rescue, a fire protection district based in St. Peters. He was no longer listed as the nonprofitâs president in an October 2019 filing with the Missouri secretary of state. Tilley did not respond to a request for comment.

Shortly after Stengerâs guilty plea, the fire district campaign fund began moving its money to a new campaign committee mentioned in the county executiveâs indictment: Regional Leadership PAC, whose treasurer was Dave Tilleyâs son, Kyle Tilley. By October, the fund had moved $37,000 to the new committee, all in increments of $5,000 or less, which donât trigger large donation alerts with ethics regulators.

The fire district fund then dissolved in October. The Regional Leadership PAC has spent little since then, and $52,000 sat in its account at the end of the year. Kyle Tilley, who is no longer listed as treasurer of the PAC, did not return a call seeking comment.

Central County Assistant Chief of Administration Gary Donovan, the treasurer for the fire district fund and secretary for the Missouri Association of Career Fire Protection Districts nonprofit, did not respond to requests for comment about the new campaign finance disclosures.

In November last year, a month after the campaign committee dissolved, it filed an amendment disclosing that the Oct. 20, 2018, donation of $250,000 actually came from Great St. Louis, the nonprofit affiliated with Sinquefield.

Great St. Louisâ $450,000 contributed to the fire district committee, plus the $150,000 to the carpenters union and $100,000 to the county Prop P fund put the sum at $700,000, the amount Stenger said Sinquefield donated to his efforts.

In his emailed response to questions, Brown, Great St. Louisâ president, said he didnât know why the fire district committee filed the November amendment with the state ethics commission. Great St. Louis donated to both the carpenters union and the county Prop P fund because âthey requested a donation,â he said.