ST. LOUIS • As new details emerged Saturday on plans for a , two things became clear:

The financing plan suggested by Gov. Jay Nixon’s two-man team could work, analysts and insiders said. It’s been done before.

But that’s not the hard part.

Now stadium advocates need to pin down details, experts said. They need to secure funding. They need a realistic plan to buy land on the north riverfront.

“I see it as a plan that should be discussed. It’s not such a no-brainer that it should be accepted yesterday,” said Marc Ganis, a stadium consultant who sat on the negotiating teams that brought the Rams to St. Louis and sent the Raiders back to Oakland. “It’s a reasonable starting point for meaningful discussion.”

People are also reading…

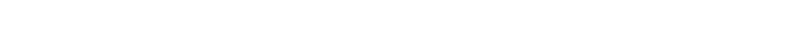

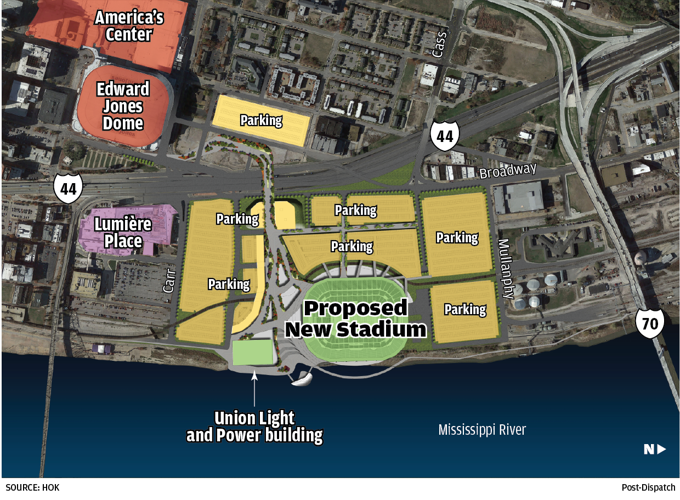

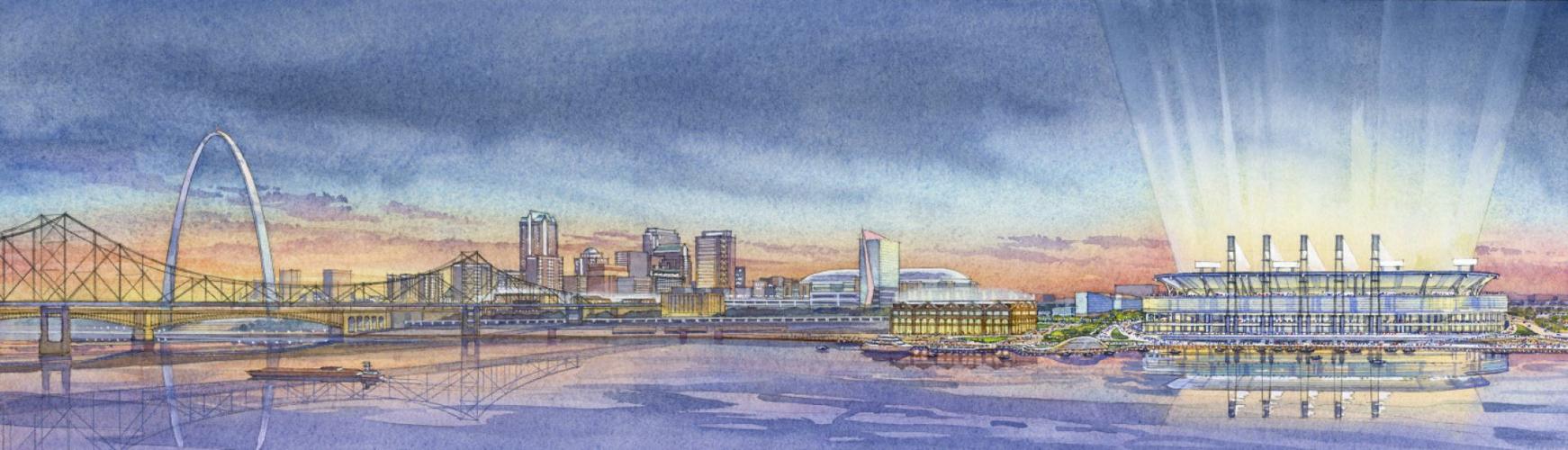

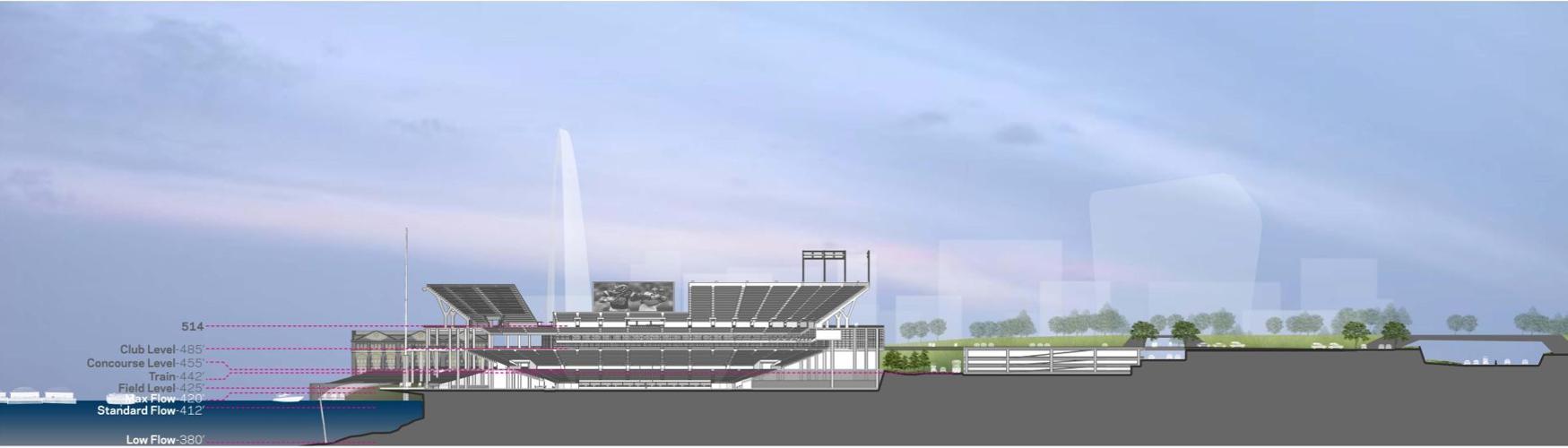

On Friday, Edward Jones Dome attorney Robert Blitz and former Anheuser-Busch President David Peacock announced a vision to keep football in St. Louis: A 64,000-seat open-air stadium on the Mississippi River, above the high-water mark, with a floating riverfront trail, boat docks and more than 10,000 parking spaces for tailgaters.

The 90-acre facility would cost between $860 million and $985 million, the plan estimated.

Peacock and Blitz outlined funding sources, including $200 million from the National Football League’s loan program, most of which would likely be paid back by the team; as much as $250 million from Rams owner Stan Kroenke; and as much as $55 million in state tax credits.

The funding includes two streams of money from the region’s residents:

• About $130 million in the sale of personal seat licenses, which reserve specific seats for fans and are often necessary to buy season tickets.

• As much as $350 million from the extension of the bonds at the Edward Jones Dome, where the Rams now play.

Specifics were few, and details vague. Blitz and Peacock, for instance, declined to describe how any new bond issue might work.

Saturday, financial analysts and stadium experts discussed with the Post-Dispatch how such deals have been done in the past.

It’s like refinancing your house, several said. Interest rates drop — and they have. You go to the bank for a new loan, at a lower rate. And you pay off the old mortgage with the new one.

The difference, in this case, is the new mortgage isn’t for the old house, but for a new one.

“The notion of an extension of bonds has been done before,” said Ganis, the stadium consultant and president of ������ƵCorp, a Chicago consulting firm.

Soldier Field, home to the Chicago Bears, for instance, used roughly $500 million in bonds for the public portion of its renovation a few years ago. And to pay down those bonds? Chicago officials redirected a hotel-motel tax that had been used on U.S. Cellular Field, where the White Sox play baseball, Ganis said. Some of the money from the new bond issue went to the White Sox ballpark, too.

Chicago got two renovations without a tax increase or public vote, Ganis said. And, at least in that, the public was happy.

There is a bit more than $100 million left on the Edward Jones Dome’s original $300 million loan. The state of Missouri now sends $12 million a year to pay it down. The city of St. Louis chips in another $6 million annually, as does St. Louis County.

DETAILS, DETAILS ...

The devil is in the details, several financial analysts warned in conversations with the paper. The exact interest rates, pay-off amounts, loan lengths and existing bond rules matter.

But, the analysts all said, $24 million a year could produce enough to pay off the Dome debt and provide $300 million or more for a new stadium.

The $130 million target for personal seat license sales seems realistic to Ganis, as well, he said on Saturday.

The business community will have to buy in, he said. They’ll have to see PSLs, as they’re called, as a community service — not payments “to enrich an already rich man.”

But Ganis said St. Louis has a leg up. Leaders have done this before, when the Rams first arrived two decades ago from Los Angeles. And the region has “an outsized number of corporate headquarters relative to its size of market,” he said.

Besides, he said, it’s a myth that the owners of big-market teams make far more money than those in smaller markets. “An NFL team can be very well supported in Green Bay, Wis., which has far fewer corporations and economic activity than St. Louis,” Ganis said. “The beauty of the NFL is the large markets end up subsidizing the small markets.”

Unlike factories and warehouses, sports facilities are more than just infrastructure. “In most cases, infrastructure investment does not also lead to the kinds of community benefits that sports does,” he said. “It brings communities together. It’s something people talk about.

“It’s part of what makes a great American city a great American city,” he continued. “It’s part of what creates a devotion to a city.”

Take Mark Taylor, 51, from Chesterfield. Twenty years ago his wife was pregnant and they were looking to save to buy a house. She forbade him from buying Rams PSLs. He did anyway, spending $12,000 on four seats. “I got in so much trouble,” he said. But Taylor, a dentist, said he’d do it again if a new stadium gets built on the riverfront.

“I love football,” he said. “I just don’t want to lose a team.”

All parties agree that there’s a lot still to figure out.

The Missouri Legislature will almost certainly have to approve public ownership of a new stadium.

An extension of the bonds may well mean a public vote in St. Louis and St. Louis County.

All of this is still being researched, said Jim Shrewsbury, chairman of the Edward Jones Dome Authority, the public body that owns the Dome, and will likely own any new stadium to come.

The plan is a good starting point, he said, echoing several on Saturday. But that’s all.

“It’s like anything else,” he said. “It’s one step in a million-mile trip.”