Most of us wouldnŌĆÖt make a big investment without expecting some kind of a return.

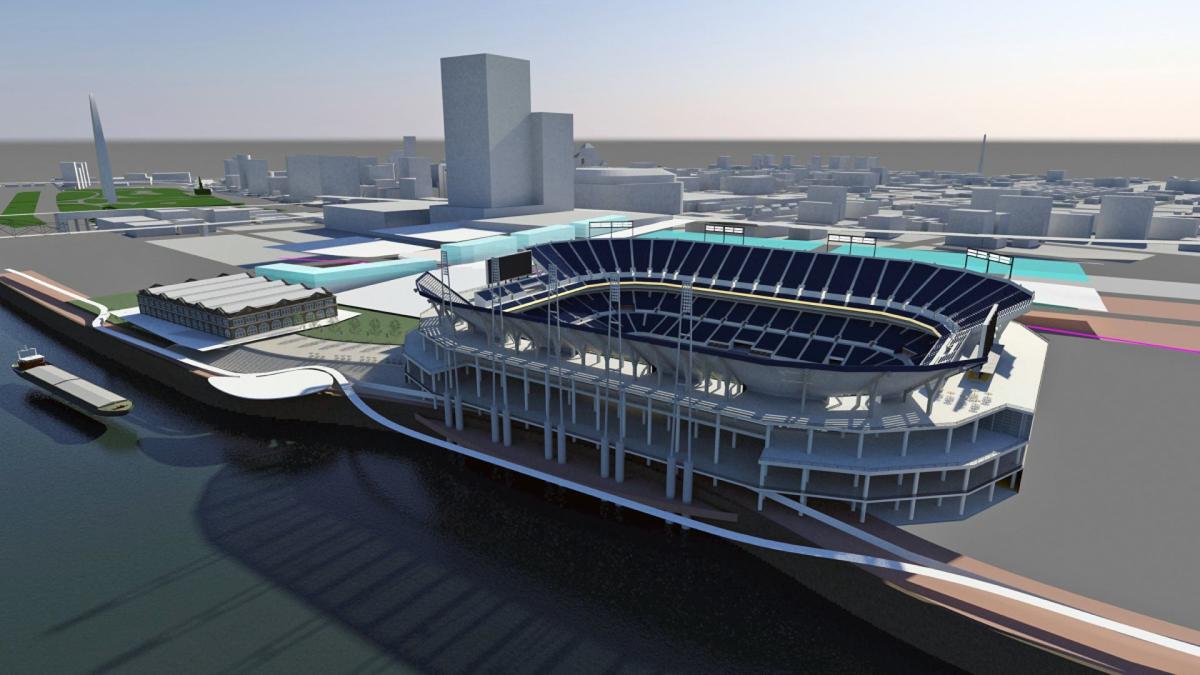

If St. Louis socks half a billion dollars into a new football stadium, however, the best it can hope for are some intangible benefits. An open-air sports palace can provide a , boost the regionŌĆÖs image and make St. Louisans feel better about their city.

All those are good things, but if you want economic benefits, professional sports are the wrong place to invest.

Study after study has found that stadiums and teams provide no measurable boost to a cityŌĆÖs economy. ŌĆ£The biggest fear is a loss of visibility for your cityŌĆØ if a team moves away, says Patrick Rishe, a professor of economics at Webster University. ŌĆ£In terms of economic loss, most people who go to the games are local, so there isnŌĆÖt any.ŌĆØ

People are also reading…

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs not a change in net spending of a magnitude to really matter to a large, diverse urban economy,ŌĆØ adds Robert Baade, an economist at Lake Forest College in suburban Chicago.

Sure, football fans buy tickets, parking and beer, but their bank accounts didnŌĆÖt magically expand to make room for that expense. They shifted money from elsewhere in their budgets.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs not as if people in non-NFL cities donŌĆÖt spend money on entertainment,ŌĆØ says Victor Matheson, professor of economics at Holy Cross College in Massachusetts.

Why, then, do cities subsidize stadiums that primarily benefit wealthy owners?

ItŌĆÖs because theyŌĆÖre negotiating with a monopoly. The NFL and its owners can threaten to take their game elsewhere, and cities fear the bad publicity that comes with losing a high-profile team.

No owner has pressed that advantage harder than Stan Kroenke of the Rams. He let it be known last week that he and a business partner want to build a stadium in Inglewood, Calif., near Los Angeles. So now St. Louis is not only trying to please Kroenke, itŌĆÖs also competing with him.

Under those circumstances, telling him to finance his own stadium simply wonŌĆÖt work. HeŌĆÖd build it in Los Angeles. The only way to keep the Rams is by opening the public purse.

Dave Peacock, the former Anheuser-Busch president who presented St. LouisŌĆÖ stadium plan Friday, tried to emphasize that the purse is not being opened very wide. He said Missourians wonŌĆÖt pay any more in taxes to finance the new building.

That may be true, but PeacockŌĆÖs plan calls for raising at least $300 million by refinancing the bonds on the Edward Jones Dome. Stretching out the bond payments, probably for 30 years, represents a real commitment of public resources. Even if tax rates donŌĆÖt rise, those bonds represent resources that canŌĆÖt be used for other needs, such as roads or schools.

The financing plan, which calls for about half the stadiumŌĆÖs cost to come from public sources, is similar to the deal the Vikings are getting in Minnesota.

Their new stadium in Minneapolis is scheduled to open in 2016, with taxpayers bearing about half the $975 million cost.

New stadiums in Dallas, New Jersey and the San Francisco area involved smaller subsidies, but those teamsŌĆÖ owners didnŌĆÖt have KroenkeŌĆÖs sense of wanderlust.

St. Louis is being asked to pay dearly for the prestige of remaining an NFL city, so I think Peacock described his stadium plan accurately when he called it a ŌĆ£crown jewel.ŌĆØ A jewel can sparkle and make its owner feel good, but itŌĆÖs hardly a productive use of half a billion dollars.