Mayor Lyda Krewson has a Workhouse conundrum of her own making.

Two announcements she made recently offer a view of two competing visions.

First, Krewson announced that her administration was for people to be able to post bonds to get out of the city’s Medium Security Institution, known as the Workhouse, more quickly.

This is a good thing. For far too long, people held on misdemeanor violations who ought to be able to post bond and get released before trial had to spend a night or a full weekend in jail, even if they could raise the bail money.

The move is likely to add to the trend, which has accelerated under Krewson’s administration, of the city’s jail population significantly dropping.

People are also reading…

Since Krewson took office, the population in the city’s two jails — the City Justice Center on Tucker Boulevard is the other one — has dropped to about 900 from 1,400. The mayor is proud of this drop.

“We have been encouraged by the continued decline in our jail population,” says her spokesman, Jacob Long.

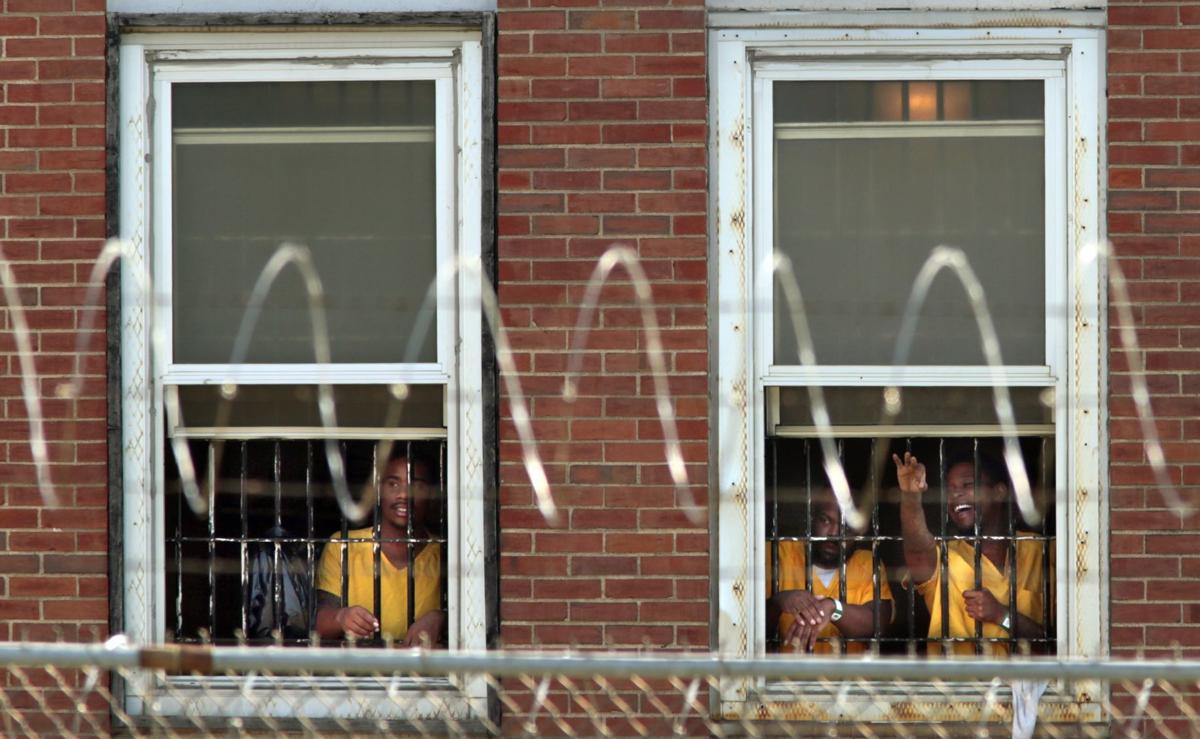

So, too, have the activists who share much of the credit for that drop in jail population, from the Close the Workhouse movement, , ArchCity Defenders, the ACLU and others. A key goal for those groups, which include many people who have stayed in the Workhouse, is to close the facility that has been subject to multiple state and federal lawsuits, including one pending now, alleging unacceptable conditions that violate the civil rights of the people incarcerated there.

Here’s where Krewson’s conundrum comes in.

Despite the decreasing population, she holds on to the fallacy that nothing is wrong at the Workhouse, and that it must remain open. Just last week she tweeted excerpts of a recent grand jury report, in which the grand jurors, after an organized tour of the facility, touted the improvements that have been made. The grand jurors went so far as to say that the Workhouse doesn’t give off a “prison” vibe.

Um, OK. The statements of each person I’ve spoken to who has been jailed there say something different. We’ll let the ongoing federal lawsuit complaining about horrific conditions play itself out.

But for the sake of argument, let’s concede that the Workhouse today is better than the Workhouse when it is overcrowded. It’s better than it was 30 years ago, better even than three years ago.

So what?

The question facing Krewson isn’t about whether the Workhouse is up to standards. She already knows it is not. That’s clear in the contract the city has with the federal government saying that its inmates can be housed at the City Justice Center but not the Workhouse.

About those federal inmates: Their numbers are dropping.

Despite an uptick in federal law enforcement activity related to a spate of shootings and carjackings in St. Louis this year, the number of federal inmates in the City Justice Center has dropped by about 40 in the past couple of months.

Why?

Money.

“The per diem is $90 a day per inmate at the City Justice Center,” says U.S. Marshal for the Eastern District John Jordan. “We have other contract facilities with lower per diem rates and therefore as inmates need less court appearances, we move some to other contract facilities to save taxpayer dollars.”

This is precisely the strategy suggested by the city’s head public defender, Mary Fox, Comptroller Darlene Green and others, when they suggested to Krewson earlier this year that she convene a group to study the eventual closing of the Workhouse.

The city balked at that suggestion, in part because it’s banking on that additional revenue from its high per diem. In comparison, St. Louis County charges $74.50 per day; St. Charles County charges $85, nearby rural jails on both sides of the Mississippi River charge even less — to pad a capital fund for future jail expansion.

In March, when Fox first suggested the idea of reducing the number of federal prisoners in the City Justice Center, the city’s overall jail population was still over 1,000 on a daily basis.

Now it’s hovering , within spitting distance of the City Justice Center’s 860 capacity. On Monday there were 891 people incarcerated in the city’s two jails; 20 of them on misdemeanor or ordinance violations.

The jail population is going to drop some more, Fox says. New bail rules instituted by the Missouri Supreme Court take effect in January, and that, too, will lead to a reduction in jail population, she says.

With just a slight continuation of the already dropping federal inmate population, “the Workhouse could be closed,” Fox says.

If only Krewson would get out of her own way, she could save the city $15 million, the approximate cost to operate the Workhouse. More money for cops and mental health workers. More money for neighborhood improvement in high poverty areas. More money for anti-violence programs. More money to keep the community safe.

That would look good in next year’s grand jury report.