ST. LOUIS â Nearly a year after three of their own were indicted for abusing their power over development, St. Louis aldermen are close to passing legislation aimed at making sure it doesnât happen again. But they wonât go nearly as far as some, including Mayor Tishaura O. Jones, had hoped.

The bill, set for a final vote Friday, has been stripped of provisions that would have formally ended a tradition that for decades gave aldermen veto power over development in their wards.

It also leaves in place rules that give aldermen veto power over applications to a $37 million program doling out grants to businesses along north St. Louis streets. That is despite the fact that those provisions were insisted upon by former Board President Lewis Reed, who admitted to taking bribes for help with development incentives, and despite Jones calling out the provision as ripe for abuse after Reed and others were indicted last summer.

People are also reading…

Nick Desideri, a spokesman for the mayor, said the office was disappointed by some of the amendments. But he said Jones still supports the legislation, pointing to added transparency measures at the cityâs economic development agency and a requirement that aldermen disclose conflicts of interest when they file development bills.

âAt the end of the day, this is still a good bill that moves the ball forward,â Desideri said.

It started its legislative life as a far more ambitious reform.

When the bill was first filed in late June, just weeks after the indictments rocked City Hall, it explicitly said letters of support from aldermen should no longer determine when the bureaucracy begins processing variance, zoning or tax abatement applications â an unwritten St. Louis tradition often referred to as âaldermanic courtesy.â Those letters came under harsh scrutiny after federal prosecutors charged Reed, Alderman Jeffrey Boyd and Alderman John Collins-Muhammad last summer for accepting cash bribes in exchange for official acts, including letters backing development tax incentives.

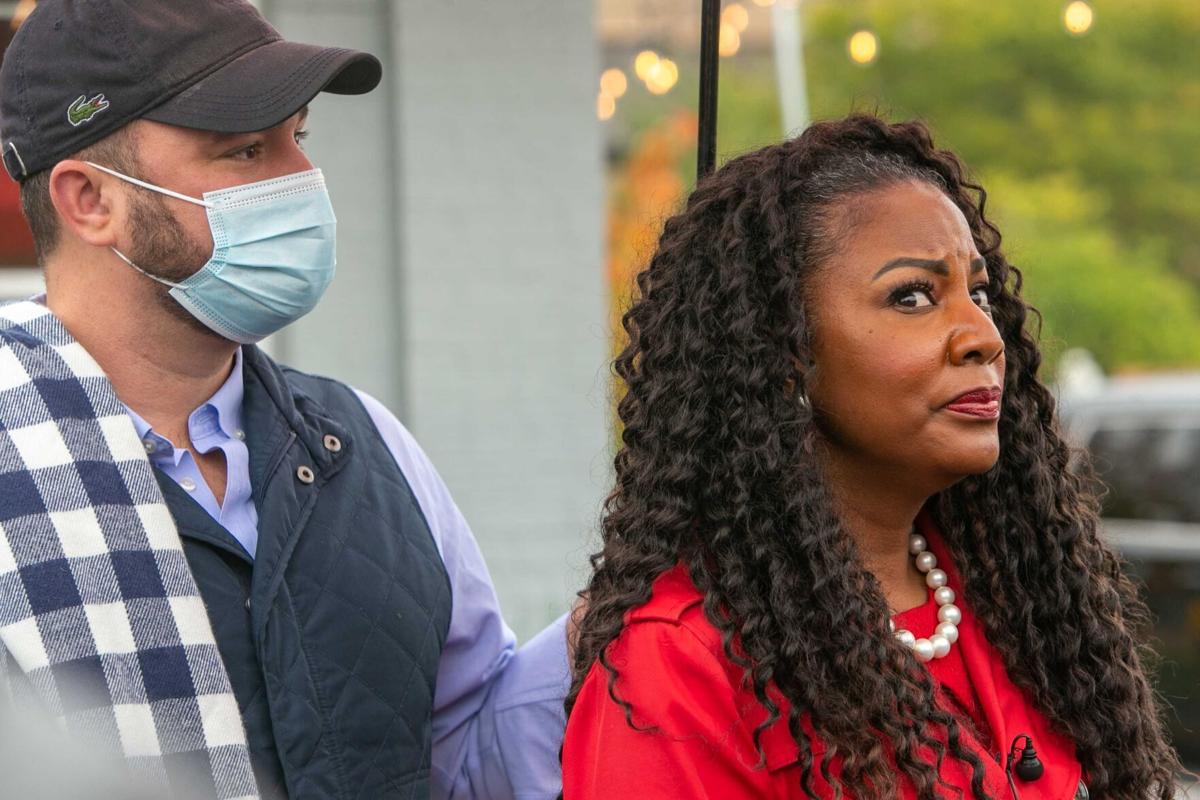

After the indictments, Jones called for change.

âNo longer can we have a process where the alderperson has ultimate veto authority,â .

But when aldermen got their hands on the reform bill, compromise came quickly.

Among provisions they removed was a proposed form letter aldermen would be required to use to lend their support to projects. They stripped out language barring aldermen from advocating for specific conditions such as the amount of tax abatement. Bill sponsor Shane Cohn argued aldermen could still put conditions on projects when they introduced legislation publicly at the board, but his colleagues pushed back against limits on how they could lobby for or against projects in their neighborhoods.

âTheyâre not in jail because they wrote letters,â Alderman Jack Coatar said of the indicted aldermen. âTheyâre in jail because they took bribes.â

The St. Louis Development Corporation was already moving away from the unofficial reliance on support letters, and aldermen may as well.

SLDC said in December it no longer will wait for aldermanic support before processing incentive requests, an administrative change it undertook after one alderman sought to hold up several large projects. And with the Board of Aldermen set to lose half its ranks this April, the scramble to keep up with double the constituents could leave less time for micromanaging.

But an unofficial policy at the Board of Adjustment requiring aldermanic support before city staff will process requests for variances â the mundane approvals needed by many construction projects for slight deviations from the building code â will remain in place after the Board of Adjustment was removed from the reform bill.

âThe Board of Adjustment in particular, thatâs an opportunity for residents to convey through their alderperson concerns or restrictions respective to businesses that are opening, so I donât think itâs necessary to limit someoneâs ability to work with their community and put conditions on certain uses,â Cohn told the Post-Dispatch.

Asked whether the administration could change that policy internally, Desideri said the city is âdoing a thorough review of all of our development policies.â

Amendments removing aldermanic involvement in the new $37 million grant program were dropped, Cohn said, after the boardâs clerk informed him the provision was unrelated to the larger bill. Desideri said the aldermanic letter language in the commercial corridors grant program was âstill a concern.â

But backers tick off improvements that remain in the bill.

The measure requires SLDC to publish recordings of its meetings online. The incentive review process SLDC has implemented in response to political pressure over the last several years will be enshrined in ordinance. And St. Louis Public Schools, the taxing jurisdiction most impacted by city incentives forgoing the future property tax revenue new development generates, must now be formally consulted for the districtâs position on large incentive deals.

Developers, too, see improvements.

âThis proposed legislation will give developers who are considering investing in the city a transparent and consistent roadmap of what they can expect in terms of potential incentives,â said David Sweeney, a Lewis Rice attorney and expert in helping developers navigate the city bureaucracy.

Michael Hamburg, who is building incentivized projects including the Target in Midtown and a new apartment building in the Central West End, said securing support from the alderman where a project is located will always be important as a proxy for neighborhood support, no matter what city ordinance says. He said the billâs attempt to codify more of the development process, however, is a positive.

âThereâs somewhat of an unknown with the city if you start a process on incentives, and every project has somewhat been treated differently,â Hamburg said. âSo I think any attempt to create a standardized roadmap with a scoring system that everyone can be on the same playing field and really understand how it works, I think itâs a step in the right direction.â

But Joe Lengyel, a small developer who struggled to get aldermanic letters of support for variances allowing him to build single family homes in Forest Park Southeast, worries about the continued reliance on unwritten rules at bodies like the Board of Adjustment. Heâs developed in St. Louis County municipalities and âthereâs no hidden, arcane processes that you have to go through.â It hasnât scared him off, but he wonders if others are hesitant to build in the city because of aldermanic courtesy.

âIf they want to keep the aldermanic privilege in there, I donât really care one way or another about that. But I do think it needs to be as simple as possible for people who are small operators like me,â Lengyel said. âIt just doesnât feel like anything is really going to change.â

PAY TO PLAY: After three St. Louis elected officials are indicted on bribery charges, Jim Gallagher and David Nicklaus say the city needs to take a hard look at policies that give individual aldermen too much control over development.