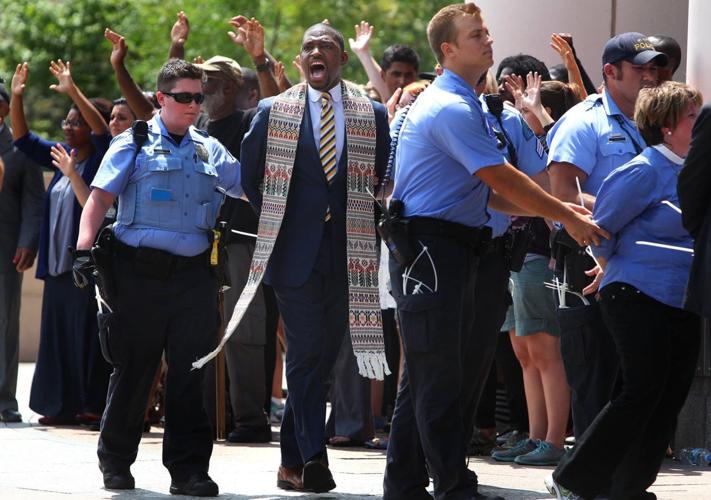

Thinking back to the second public meeting of the Ferguson Commission still brings tension to the body of the Rev. Starsky Wilson, one of the co-chairs of the organization charged with helping forge a path toward racial equity in the St. Louis region after the Aug. 9, 2014, death of Michael Brown.

It was Dec. 8, at a meeting in the Shaw neighborhood in the city of St. Louis, not far from where police had shot and killed another young Black man, 18-year-old Vonderrit Myers, sparking weeks of protest in the city. That night, there was to be a vigil for Myers nearby, and the protesters made the Ferguson Commission meeting their first stop.

One of the speakers was then St. Louis police Chief Sam Dotson, and as the chief addressed the commission, with a line of armed police officers in the back of the room along the wall, protesters made their voices heard, loudly.

People are also reading…

“It was tense,” Wilson remembers. “Josh Williams was right in the face of the chief yelling at him.”

Wilson’s phone was blowing up with texts and calls, urging him to settle things down, to ask the protesters to sit down and quietly listen to Dotson and the other speakers. Wilson, tension building, let the protesters do their thing.

It was a key moment in the validation of the and the importance of the work it would eventually produce. “We must allow people who have been harmed room to speak,” Wilson says. “Even when it’s uncomfortable and some of the rest of us have to feel the tension.”

That lesson will serve Wilson well as he takes on a new leadership role, elevating himself even further into the national civil rights discussion. On Wednesday, Wilson was announced as the new president of the in Washington, D.C., taking over for the organization’s founder, civil rights leader Marian Wright Edelman.

Edelman was the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar, and she became a key adviser to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and attorney for his Poor People’s Campaign in the height of the civil rights movement in the 1960s. She founded the Children’s Defense Fund, an organization that advocates for policies that will help children escape poverty, in 1973.

That civil rights movement has been rekindled, and the mobilization of the new movement for Black lives owes much of its start to the organization that took place on the streets of Ferguson and St. Louis, Wilson says. His new role will mirror what he has been doing here, navigating the process of crafting good public policy while building capacity for Black and brown voices to have a seat at the table.

That process, as the nation is seeing in the wake of national protests following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and the shooting of Jacob Blake, can be loud, it can be messy, but it is necessary if people are going to feel like they are being heard.

In Missouri, those voices that grew from the streets of Ferguson are having an effect, and not just in the St. Louis area. Wilson points to the success of the Close the Workhouse movement, and the statewide passage of Medicaid expansion and the increased minimum wage, all supported by young Black activists who are making a difference.

“This is all a result of the capacity we are building from that moment that started in Ferguson,” he says. Before he heads to D.C., Wilson has a bit of unfinished business in Missouri. He has become one of the key voices against Amendment 3, the attempt by Republicans in the Missouri Legislature to undo the redistricting reforms passed by voters in 2018, intended to give voters a stronger voice by drawing fairer, more balanced legislative boundaries. One of the things Amendment 3 would do if it passed, is for the first time in the nation’s history, not count children in the process of drawing legislative maps.

“They are trying to act as if children in the state don’t exist,” Wilson said. “They’re writing young people out of the process of democracy.”

One of those young people is Wilson’s 15-year-old son, who can’t vote this November, but will be able to by the next presidential election, which will be affected by the new maps drawn following the 2020 census. Wilson hopes Missouri voters stand up and defend their Clean Missouri vote by defeating Amendment 3. It’s his last stand for Missouri children before he becomes the leading voice for children in the nation’s capital.