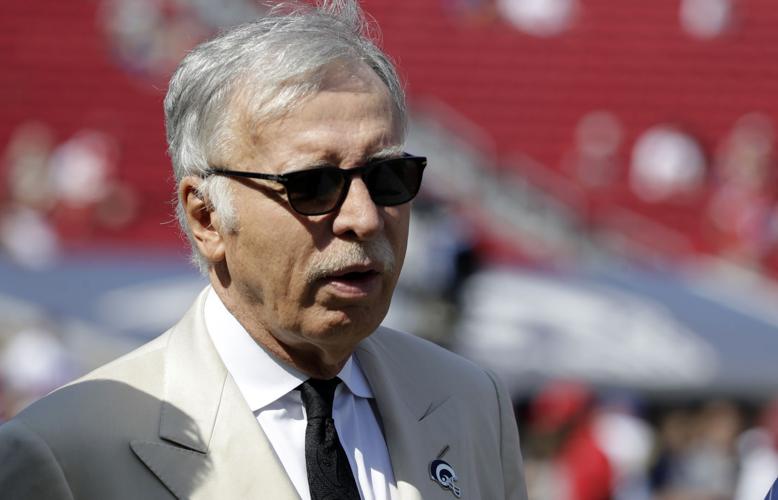

ST. LOUIS — The National Football League, Los Angeles Rams and mega-billionaire Stanley Kroenke, maneuvering to avoid a high-stakes civil trial, have filed court pleadings urging a judge to reject claims that NFL team owners broke league rules and lied to the public about the Rams’ departure from St. Louis.

In the filings, the league, Rams and Kroenke say NFL relocation guidelines establishing a process for teams seeking new host cities are merely internal guidelines that club owners “may” consider when evaluating proposed moves. Ultimately, they said, owners should apply their “business judgment” to advance the NFL’s “collective interests.”

The NFL’s decades-old policies, they say, aren’t a contract at all, meaning St. Louisans deserve no compensation from the fallout over the Rams’ 2016 move to Southern California and hold no claim to league profits resulting from the relocation, according to legal briefs seeking to end the lawsuit filed by St. Louis and St. Louis County more than four years ago.

People are also reading…

“None of these amounts came from plaintiffs or at their expense,” according to a filing seeking to dismiss the suit. “Nor would they ever go to plaintiffs under any circumstance.”

Documents in the case, which has stretched for more than four years, have nearly all been filed under seal, meant to keep the information private. But the Post-Dispatch obtained the filings Wednesday from the St. Louis Circuit Court before they were sealed to the public.

Lawyers for the Rams and the NFL did not return phone calls Friday. Chris Bauman, a lawyer for the city of St. Louis and other plaintiffs, declined comment. Left unexplained was how the documents were filed publicly before they were all sealed hours later. A judge has previously ordered that many documents containing evidence be sealed.

The material includes internal NFL evaluations of stadium proposals and economic projections, memoranda among NFL executives and partial deposition testimony from executives involved in the Rams’ years-long relocation saga. Plaintiffs will have a chance to respond with filings of their own.

The documents show how early and how clearly Kroenke was focused on moving the Rams to Los Angeles. They spell out in stark detail how poorly the region’s proposed riverfront stadium — a last-gasp effort to keep the Rams — fared in the eyes not just of Kroenke but of NFL executives, too. Together, the court filings offer a glimpse into the secret relocation talks among NFL executives who ultimately authorized the Rams’ move and into their views of competing team bids to hop into the lucrative Los Angeles market.

The lawsuit brought by St. Louis, St. Louis County and the St. Louis Regional Convention and ������Ƶ Complex Authority in 2017 is set for trial in January in St. Louis. Its core claim: that the NFL broke its own relocation rules that were established decades ago to avoid antitrust liability and encourage teams to work to stay in their home cities.

The suit alleges the Rams’ move to Los Angeles cost St. Louis millions annually in amusement and tax revenue and thousands of construction jobs that would have been created to build a new riverfront stadium. The Regional ������Ƶ Authority, or RSA, owns The Dome at America’s Center, formerly called Edward Jones Dome, where the Rams played for 21 seasons — 15 of them with losing records. The St. Louis Convention and Visitors Commission, often called the CVC, runs the stadium and convention center.

NFL plays defense

Kroenke in a controversial secret vote in 2016 swayed at least 75% of NFL club owners to approve the team’s move to Los Angeles. Kroenke’s escape clause was a provision in the 1995 lease of the Edward Jones Dome that the state of Missouri, city of St. Louis and St. Louis County must renovate the dome for $700 million to make it a “first tier” stadium, on par with the top eight stadiums in the league. But local officials ultimately declined to make the preferred renovations, opening the door for the Rams to operate on a year-to-year basis at the dome.

In the NFL’s motion for summary judgment — a common legal strategy in civil suits to avoid trial — the NFL, Rams and Kroenke broadly outline their defense against claims they violated a contract with St. Louis, improperly profited from the move to Los Angeles and interfered with the business relationship between St. Louis municipal leaders and the Rams club.

First, the NFL argues its relocation rules are internal policies created “unilaterally” by and for the league, therefore there’s no claim the league broke a contract with public entities that paid to bring the team here in the mid-1990s.

“Indeed, the undisputed evidence shows that the NFL’s primary purpose in promulgating the policy was to benefit the league and its member clubs,” its filing says.

Second, the NFL contends St. Louis and St. Louis County have no right to any of the league’s or teams’ profits from the Rams’ move because they would never have collected any of the $550 million relocation fee the Rams paid other NFL franchises and have spent nothing toward the development of Kroenke’s $5 billion SoFi Stadium at Hollywood Park in Inglewood, California.

The documents also say a judge should reject the claims Kroenke and NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell cost St. Louis millions because of false public statements about the Rams’ intentions, claiming St. Louis leaders knew of the team’s disinterest in the riverfront stadium plan. Goodell's and Kroenke’s public statements, the filings say, “were truthful, non-actionable statements of opinion about the NFL’s own internal policies and procedures.”

The St. Louis plaintiffs can’t prove claims the NFL and Kroenke interfered with St. Louis’ business relationship with the Rams because city and county officials “were aware that the Rams’ relocation was a distinct possibility” when the NFL approved the Rams’ move and because Kroenke “can’t be held liable for interfering with his own business relationship,” the documents say.

“The evidence is undisputed that Mr. Kroenke acted at all times within the scope of his authority as the Rams’ owner and chairman for the economic benefit of the Rams when seeking to relocate,” the NFL’s motion says.

Finally, the NFL argues St. Louis County can’t claim damages because it didn’t contribute to the cost of developing the proposed $1.1 billion riverfront stadium plan. A two-man task force appointed by former Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon to plan a new stadium in St. Louis cost taxpayers at least $16.2 million.

The court filings include several internal NFL documents and memos including Goodell’s January 2016 report to the league’s that evaluated relocation proposals from the Rams, the then-San Diego Chargers and the then-Oakland Raiders.

Goodell’s report came just days after Kroenke sharply criticized St. Louis in his relocation proposal. Goodell described the Edward Jones Dome as inadequate for the NFL and cited tepid population growth for the St. Louis region, sluggish ticket sales and the Rams’ underperforming finances. His report additionally questioned the long-term viability of the riverfront stadium.

“The Rams have estimated that the club’s overall financial position would deteriorate under the proposal, even utilizing the revenue projections of the public authorities,” Goodell wrote. “The factors discussed above — including the size of private investment required in this market (including additional amounts from the league) and the risk attributable to political opposition — raise significant concerns about the certainty and long-term viability of the Task Force’s stadium proposal to retain the Rams.”

‘Our only remedy’

After the NFL approved Kroenke’s plan, Kroenke said publicly that the riverfront stadium proposal was so bad that any NFL team taking that deal would be headed for “financial ruin.” Officials were outraged. Fans were heartbroken.

It had long been rumored that Kroenke had to sign a contract protecting the league and all of its teams from a lawsuit stemming from the Rams’ departure. But the documents filed Wednesday publicly spell out for the first time just such an indemnification agreement. In a copy of the league’s relocation policy sent in 2014 to Chargers owner Dean Spanos, the document says that if NFL or team profits are threatened, the relocating club “will be required to indemnify other members of the League for adverse effects that could result from the proposed relocation.”

In their filings, the NFL compares the St. Louis lawsuit to that of a 2018 federal antitrust suit the city of Oakland filed against the Raiders and the NFL over the team’s move to Las Vegas. A California judge threw out the case in April 2020, saying the city wasn’t entitled to damages.

Missouri courts have blocked the NFL, Rams and Kroenke’s repeated efforts to expand the scope of the lawsuit to include evidence about the Rams’ 1995 dome lease and the 2013 arbitration that sided with the team’s desire to renovate the dome into a first-tier stadium. The new court filings include letters from 2013 between Rams executive Kevin Demoff and CVC officials discussing a decision against upgrading the dome and the Rams’ intention to move to an annual lease or potentially relocate the team in 2015.

Months later, the lawsuit said, after Kroenke , Demoff was quoted as saying the purchase was “not a piece of land that’s any good for a football stadium,” that there’s a “one-in-million chance” the Rams would move, and that Kroenke “is still looking at lots of pieces of land around the world right now and none of them are for football teams.”

Among the NFL executives deposed in the lawsuit were Goodell, former NFL Vice President Eric Grubman and the rarely quoted Kroenke himself, all of whom addressed negotiations over proposed dome upgrades.

“We weren’t getting anywhere obviously,” Kroenke said, testifying that because the RSA and CVC were not going to implement an expensive renovation plan, “we had our remedy which was 10 one-year options to occupy the stadium in St. Louis and our only remedy, which was to relocate.”

A lawyer for the plaintiffs, Robert Blitz, then asked Kroenke whether he spoke to any other NFL owners about moving to Los Angeles before October 2013, according to the documents.

“Prior to October of 2013?” Kroenke said.

“Right,” Blitz said.

“Prior to October of 2013 did I ever talk to anyone, any owner about the opportunity or the option to move to LA? I think I probably did,” Kroenke said.

Grubman, who has previously described the NFL as a “league of rules” in approving relocations, suggested in his April deposition that team owners, in practice, have broader discretion to make such decisions, saying “each owner is entitled to take into account any and all matters and information that the owner considers relevant.”

With seven months before the case is set for trial, legal scholars have told the Post-Dispatch that most civil suits settle first and that the NFL suit may do the same. One of the NFL’s chief concerns, said sports law professor , should be having its internal policies litigated in court.

“I think the NFL would not want to see its relocation policies be actionable,” Standen said. “Those are internal rules that typically courts are saying ‘we’re not going to base a lawsuit on that.’ Lawsuits are based on public rules, statutes.”

He believes if St. Louis and St. Louis County’s case survives the NFL’s motion for summary judgment, then they will seek to try the case.

“Because they’re public plaintiffs, I would think they want to make their point,” he said. “That’s what trials are for, to have a public airing of their grievances and to seek repose.”

, a St. Louis lawyer and adjunct law professor at St. Louis University, said the NFL has to consider whether settling the case with St. Louis would set a precedent for NFL franchises in the future.

“If you settle this case before trial, is it going to be the cost of doing business in the future?” Broshuis said. “Whenever there’s another franchise relocation, that you have to pay the prior city? I think that’s something that you’re worried about in the NFL.”