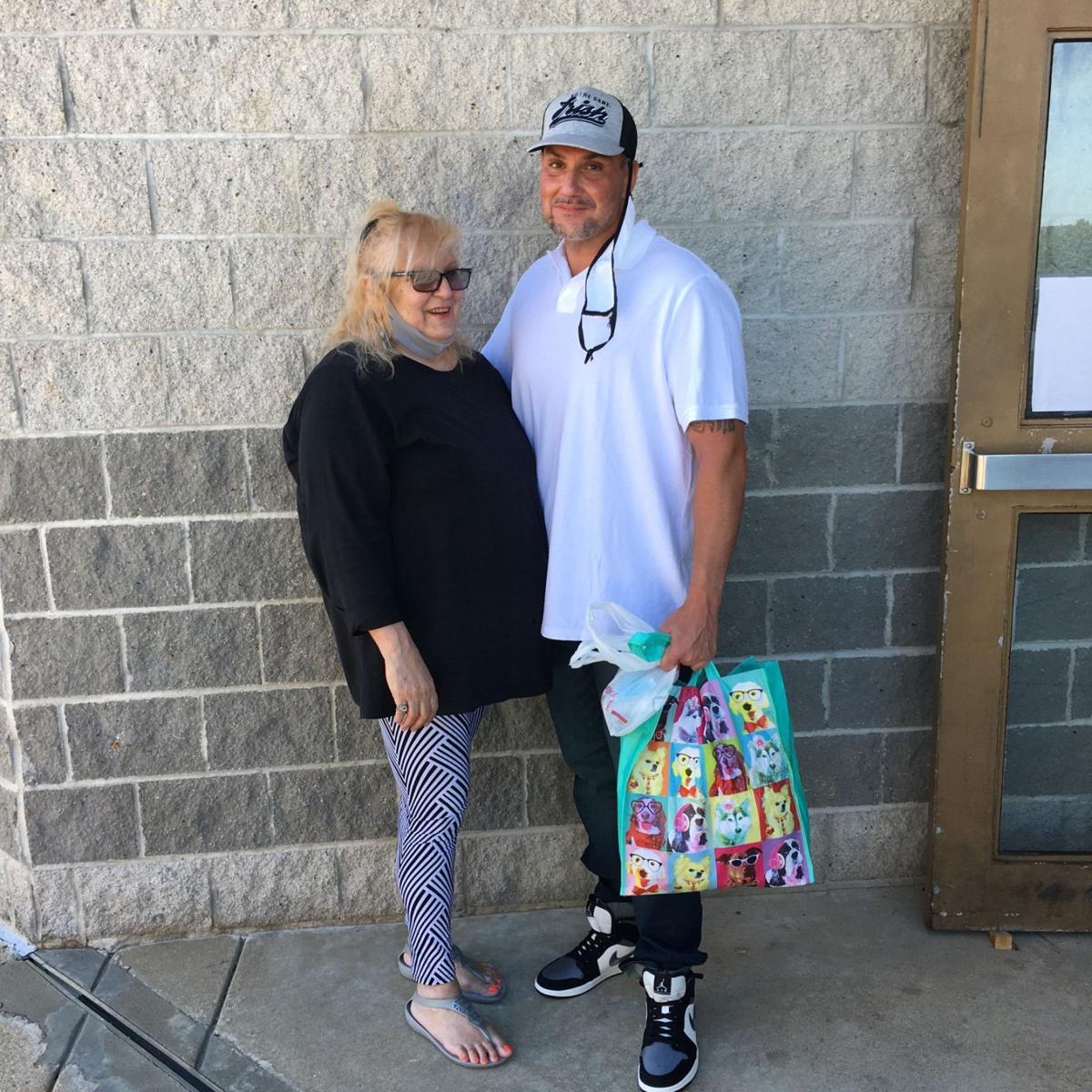

Larry Callanan walked out of the Potosi Correctional Center a free man, and the first thing he did was violate the new social norms.

He hugged everybody he could find. Social distancing be damned.

He hugged his mom, Harriet Ojile. He hugged his attorneys, Cheryl Pilate and Lindsay Runnels. He hugged his investigator, John Hefele.

“It was so intense it is hard to put it in words,” Callanan told me Friday in a Zoom video interview from his mother’s home in suburban St. Louis. “It was like a dream. I didn’t want to wake up.”

For the previous 24 years, his life had been a nightmare.

In 1996, Callanan was convicted of murdering John M. Schuh at a party they had attended in Spanish Lake. Callanan was 19 at the time of the crime, the son and grandson of somewhat notorious union officials who had suspected mob ties. His father’s legs were blown off in a car bomb explosion.

People are also reading…

From the beginning, Callanan proclaimed his innocence.

Despite the lack of a murder weapon or eyewitnesses, then-St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Bob McCulloch took the case to trial and won.

But the assistant prosecutor who handled the case, Dan Diemer, cheated to get the conviction. That was the damning conclusion reached by a judge appointed by the Missouri Supreme Court more than two decades later who examined the case. That judge, Gael D. Wood, found “egregious” prosecutorial misconduct in the case, most importantly the suppression of witness testimony that cast doubt on Callanan’s guilt.

“The clear result is a verdict not worthy of confidence, a verdict that has deprived Petitioner of his liberty for life,” Wood wrote. “At a minimum, Callanan deserves a trial free from constitutional error.”

There will be no new trial.

In fact, the new prosecutor in St. Louis County, Wesley Bell, helped pave the way for Callanan to be set free. Several months ago, Bell’s office investigated the case and determined that the prosecutorial misconduct was so bad that he wrote a letter to the court urging the court to erase the conviction.

So Callanan is home, living with his mother, coming back to a world that is very different than the one he left. He realizes that even with the conviction being erased, he always will carry the scarlet letter of having been accused of a heinous crime.

Schuh’s family still believes in his guilt. Schuh’s son, Justin, asked that if anybody has any information on the death of his father to please contact him on social media.

I feel for Schuh. A few years ago a man who had been convicted of murdering my friend and colleague was released on a Brady violation, his conviction vacated. I still struggle with the question of his guilt, because I covered every minute of the trial, but I believe the law required him to be set free.

“I wish there was some way that I could get them to wrap their arms around the truth,” Callanan said.

In the meantime, he’s grateful to be home and is trying to focus on positive things.

He’s returned to a “different world,” one consumed in two pandemics — from the coronavirus that has us all avoiding hugs and human connection, to the mass protests happening worldwide after the death of George Floyd.

Then there’s the technology. He went to prison about 10 years before the release of the first smartphone. Now he’s doing Zoom interviews.

It’s a lot to take in. In the meantime, as he tries to figure out what to do with his life, his case stands as an example of a new trend in criminal justice reform in which newly elected prosecutors such as Bell take a look at old cases. When they find errors of justice they try to fix them, rather than defend the original prosecution at all costs.

Dozens of men and women have been released from prison in the past few years because of the work of conviction integrity units. Often those cases start with a motivated man stuck in prison, spending hours in the library, trying to find answers in the law.

Callanan found his answers.

“I lived in a state of perpetual uncertainty,” he said. “I wasn’t confident until I walked out the prison doors.”