JEFFERSON CITY • Rex Sinquefield has become a household name in Missouri political circles.

Dropping five- and six-figure checks, he plows millions of dollars a year into contributions to state and local candidates and causes. But he doesn't stop there.

To sell his free-market philosophy, he finances a phalanx of lobbyists, think tank experts, public relations staffers and university economists.

Sinquefield even gutted and painstakingly restored a three-story brick house on Washington Place near Forest Park to serve as sleek, high-tech office space for his ever-growing team.

But so far, he doesn't have much to show for nearly $12 million in political contributions and more than four years of work.

Missouri legislators adjourned in May without voting on his initiatives to replace the state income tax with a broader sales tax or to increase choice in urban education.

People are also reading…

Although he claims small victories in education policy in previous years, the man who made his fortune in investing could be viewed as one of the least effective political investors ever.

But Sinquefield isn't discouraged.

In fact, Rex Inc. is enthusiastically forging ahead on a variety of fronts. The keystone of his economic policy agenda, a measure aimed at repealing the St. Louis city earnings tax, is likely to be on the statewide ballot this fall because of an initiative petition drive he underwrote.

Though he has plenty of critics, especially among organized labor and public education advocates, some Democrats praise him for fostering debate about reviving the city. Count veteran Democratic political consultant Mike Kelley in that camp.

"He clearly cares about Missouri," Kelley said. "I don't know if he can be measured too successful at this point, but if you look at his strategy, I think this man's running a marathon and not a sprint."

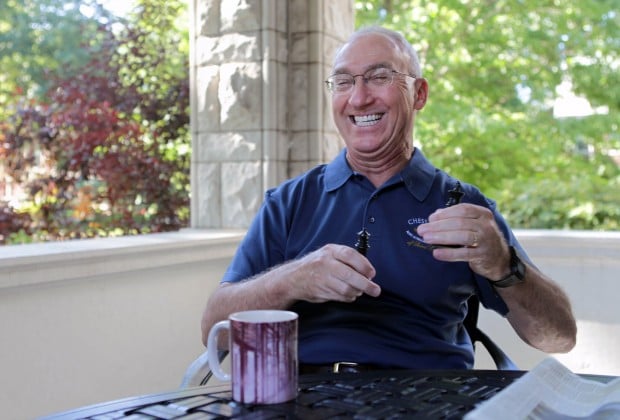

Sinquefield contends he is making progress. In a recent interview in his Central West End mansion, he credited his lobbyists and their three-year-old firm — Pelopidas — with changing the tenor of the debate in Jefferson City.

"The big difference from before Pelopidas got together and now is that we're playing offense and the other side is constantly and chronically playing defense," Sinquefield said. "And I think we move the ball down the field every year a bit more. And my guess is that pretty soon, we're going to be looking to go into the end zone."

GROWING UP IN ORPHANAGE

His personal story helps explain his tenacity.

When he was 7, his widowed mother couldn't afford to care for him and his younger brother, so she took them to the St. Vincent orphanage in Normandy. Rex Sinquefield lived there, under the nuns' tutelage, for about six years. He moved back home when he started high school at Bishop DuBourg.

He gave seminary a try before finding his niche in business and finance. He got an undergraduate degree from St. Louis University. While earning an MBA in finance at the University of Chicago, he became a fan of the investment strategy of indexing, which sticks with a portfolio that mimics the market rather than tries to beat it.

The cash Sinquefield now hands out to politicians flows from the success of Dimensional Fund Advisors, a money management firm he co-founded in 1981 in Santa Monica, Calif. By the time he retired in 2005, it had become one of the largest institutional fund managers in the country.

Sinquefield, 65, decided to return home and begin his next quest: revamping Missouri's tax and education structure.

His own company had just decided to move to Texas because that state had no income tax. Sinquefield was certain Missouri could better compete for jobs if it, too, abolished its income tax.

What ties his various philosophical issues together is his belief in individual freedom from government regulation, a theme that underlies his contention that income taxes discourage productivity and that a monopolistic public school system spawns mediocrity — or worse.

Thus, he champions letting parents choose where they send their children to school and providing tuition tax credits if they choose private ones.

So he moved back to Missouri. Now, Sinquefield and his wife, Jeanne, split their time between their Central West End home and an Osage County estate his staff calls "the farm." It is near Jefferson City and Columbia, where she plays bass in three symphonies.

In keeping with their passions, the Sinquefields have lavished money on parochial school scholarships for needy children, a music composition program at the University of Missouri-Columbia and an elaborate chess center in St. Louis, the latter to celebrate his hobby.

Their philanthropy spurs warm accolades. It's his political investments that have drawn fire.

INVESTING IN POLITICIANS

Sinquefield began making eye-popping donations — such as $100,000 to a committee linked to then-House Speaker Rod Jetton, R-Marble Hill — in early 2007.

Later that year, when Missouri briefly had campaign finance limits, Sinquefield established more than 100 political committees so that each could give his favored candidates the maximum.

Today, with no limits in place, Sinquefield writes checks of $25,000 or $50,000 to local and state officials. Recipients have ranged from St. Louis Mayor Francis Slay, a Democrat, to Lt. Gov. Peter Kinder, a Republican.

"The only reason we give it to them is because they have very similar views and often, they have enough leadership that they're going to try to get those things actuated into legislation," Sinquefield said in the recent interview.

(Gov. Jay Nixon has not received contributions from Sinquefield.)

Overall, since he returned to Missouri in 2006, Sinquefield's lobbying firm says he has spent $11.75 million on political contributions. A little more than half of the money went to issue-based campaigns rather than candidates.

The biggest chunk — $6.8 million — is funding the campaign to repeal the city earnings taxes in St. Louis and Kansas City.

Sen. Brad Lager, R-Savannah, who received $5,001 last November, lauds Sinquefield for "putting big thoughts out there. All too often in government, people just come with the complaints, not alternative solutions."

Sinquefield's five lobbyists occasionally pick up tabs for legislators and their staffs — notably $3,335 for "entertainment" in April, according to a report filed with the Missouri Ethics Commission.

But wining and dining isn't his chief tactic. Rather, Sinquefield finances a think tank, the Clayton-based Show-Me Institute, to churn out policy studies on everything from movie tax credits to an autism insurance mandate.

He also employs a public relations arm, headed by Laura Slay, a cousin of Mayor Slay, and the Pelopidas lobbying firm, anchored by Travis Brown and former Rep. Carl Bearden, R-St. Charles. (The lobbying firm's name is a Greek reference to freedom fighters.)

Sinquefield said he was learning to be patient.

"I guess that's the big surprise — that things are going to take longer than I thought. It's pretty easy to produce good ideas and get them crafted, even in immense detail. But persuading the Legislature is a bit more arduous."

TAX PLAN QUESTIONED

Critics say his plan to eliminate the state income tax is full of problems.

Senators shelved it this year after a few hours of debate over questions about replacing the roughly $6 billion in revenue that would be lost.

Sinquefield favors levying a higher sales tax on a much broader base of goods and services — everything from child care to new homes. Some type of rebates would be given to cover taxes on necessities, up to the poverty levels.

But opponents said that the proposed subsidy was inadequate and that higher sales taxes would hurt the poor. Also, it's unclear exactly which services would be taxed and whether a higher sales tax rate would push sales to neighboring states.

"The math just doesn't work," said Sen. Joan Bray, D-University City. "The tax rate would have to be too high."

Sinquefield dismissed the concerns. He said he was pleased that the bill got 'serious debate."

As for his successes, he cited education bills from previous years that permitted alternative certification for teachers and a merit pay program for St. Louis teachers.

Brown, Bearden and Laura Slay sat in on the interview. Brown interjected that the biggest victory on education this year "was what didn't happen."

"That's right," Sinquefield agreed. He cited a proposed constitutional amendment to merge the state departments of higher education and elementary and secondary education.

He said he helped kill it because higher education could have lost clout in the consolidation, jeopardizing scholarships to students at private universities.

GOING STRAIGHT TO VOTERS

His current priority — getting rid of the city earnings tax — aims to bypass the Legislature and go straight to voters.

He financed the petition drive seeking to repeal the 1 percent taxes in both St. Louis and Kansas City. The petitions are awaiting certification by the secretary of state.

If the question goes on the statewide ballot in November and a majority of voters approve it, municipal voters in both cities will consider next year whether to phase out their earnings taxes over 11 years.

The question no one has answered is how to replace the money, which makes up one-third of the city's general budget fund in St. Louis.

A study that Sinquefield financed listed options, such as broadening the sales tax base to cover various services, imposing a city tax on rental cars and raising the property tax rate.

He also suggests exploring the selling or leasing of city assets, such as Lambert-St. Louis International Airport.

"You have to keep in mind: If it does pass in the city, they've got almost 11 years to figure this out," Sinquefield said. "I can't imagine any project that can't be solved in 11 years."

He said he has heard the accusations — that he's destroying the police and fire departments and that he doesn't care about the city.

"Well, that's just a stupid statement. There's so many of those, we're not going to even bother to respond. I think the best defense against an idiot is to let them talk. Buy them air time," he quips.

Sinquefield has lined up a firm called Winner & Mandabach of Santa Monica, Calif., to run the anti-earnings tax campaign. In 2006, the company handled the successful campaign to protect stem cell research in Missouri.

That campaign broke state records, costing about $31 million. Sinquefield said he wasn't sure how much he would spend on the anti-earnings tax effort, but he promises: "We're not spending $31 million."

The campaign is called "Let Voters Decide."

Already, its slick brochures adorn the table inside the front door of his lobbyists' offices on Washington Place.

His adversaries worry that with a seemingly limitless wallet, he'll force the state income tax issue to the ballot next — in 2012. His ability to single-handedly propel fundamental change troubles Sen. Jolie Justus, D-Kansas City.

"Right now, he doesn't have a lot to show for the amount of money he's spent," she said. "But I do think, if you keep pouring money in, you're going to get somewhere."