The timing of my first meeting with dozens of small-town St. Louis County mayors who are now fighting talk of future consolidation couldn’t have been much worse.

It was in February 2014 at the Sunset Hills Community Center. The meeting had been set up a few weeks in advance. I was the editorial page editor at the time and the mayors had heard recently from the leaders of the nascent group, which was formed to study whether the divided government that defines the St. Louis region makes much sense.

The morning of our meeting, the editorial page had published an editorial I had written of the 24 school districts in St. Louis County into one unified district. The argument was based on a statewide commission from the 1960s — the Spainhower Commission — that reached the same conclusion.

People are also reading…

So it was in this context that I met Mayor Monica Huddleston of Greendale and James Knowles of Ferguson and Kevin Buchek of Bel-Nor, and a dozen or so other mayors who are part of a subset of smaller cities that make up the .

Here’s the thing: ������Ƶ were very gracious. They clearly care about their cities, each of the mayors I met, and on many objective measures, they’re doing a good job. But there’s a huge leap between the argument that City A does a great job plowing snow to the one that says it makes sense for St. Louis County to be divided into 90 different municipalities.

And that’s why the creation of a new nonprofit group by these mayors, called , is a disappointing public relations ploy that recalls some of the region’s most disappointing history.

From the beginning the mayors and city managers in St. Louis County were suspicious of the Better Together group, in part because of its strong affiliation with billionaire political activist Rex Sinquefield. As I told the mayors on that February night in 2014, I share that concern.

I’ve spent a significant amount of time in the past few years fighting all things Rex. I find most of his agenda abhorrent and believe the amount of money he throws around in Missouri politics is both obscene and dangerous.

But one doesn’t have to rely on the reports created by Better Together to know instinctively that if St. Louis were starting from scratch, there is no way it would devise a government system like the one we have, with dozens of police and fire departments, 80 municipal courts, and the region’s largest city, St. Louis, separated from the county that also bears its name.

Here’s how the highly respected Police Executive Research Forum described the fragmentation in police departments in St. Louis in its report earlier this year:

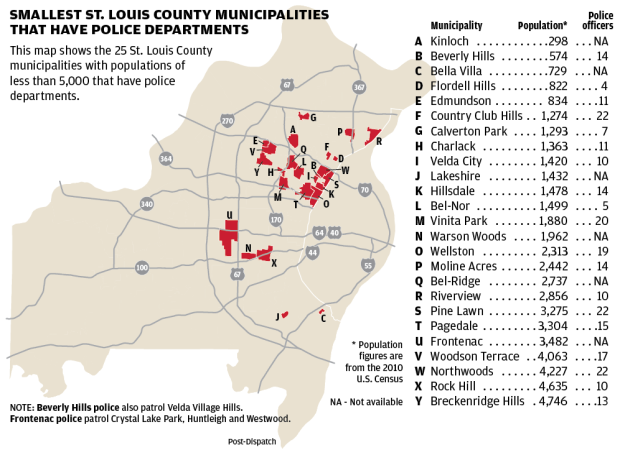

“PERF has never before encountered what we have seen in parts of St. Louis County,” . “The fragmentation of policing among 60 separate police agencies, many of which are extremely small, causes inefficiencies and uneven delivery of police services to area residents. … The fragmentation in the St. Louis region is extreme.”

And that’s just policing.

Since Aug. 9, 2014, the region has become acutely aware of the problems in its municipal courts. Now, all three branches of Missouri government are working to reduce the oppression such courts are placing on the citizens, many of whom are used as fundraising sources as traditional municipal revenue sources dry up.

And then there’s economic development. Long ago, the East-West Gateway Council of Governments identified the practice of cities’ using tax increment finance districts in St. Louis County to lure big box stores from municipality to municipality as a destructive process that simply doesn’t .

Earlier this year, the internationally respected Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development produced a study called It examined cities worldwide and found that those with fragmented government produced much less economic growth than cities with more unified government. Why? A divided region fights among itself rather than raising one tide to lift all ships.

Fractured government, the study found, decreases labor productivity and increases income inequality and racial division.

It’s those last two issues that were at the center of the Spainhower Commission report that I wrote about on the day I went to see the mayors. In the 1960s, a panel of statewide and national experts determined that the inequality and racial divisions in St. Louis schools (and others in the state) were a direct result of the districts’ being so divided by geography. They recommended unity so that taxpayers in all parts of the city were invested in the success of every child, no matter how poor, or black, that child might be.

Nothing happened, of course, in part because when challenged, dozens of local government bodies fought for their survival at the expense of doing what was right for the children.

Decades later — with the same problems persisting in a region divided by geography, race and money — history is repeating itself.