Ask Stephanie Lummus about the all-too-common practice of jailing men and women who are behind on their child support and she is quick with a reason as to why it is generally a bad idea.

“It breaks families apart,” Lummus says.

A lawyer with , Catholic Legal Assistance Ministry, Lummus represents many clients — nearly all of them living in poverty — who end up being targeted by prosecutors for criminal charges in child support cases. Except in those extreme cases where a parent of means is simply refusing to support his children, such prosecutions invariably backfire, she says.

“We’re hamstringing the very people who we want to go out and get a job,” Lummus says. “It’s self-defeating.”

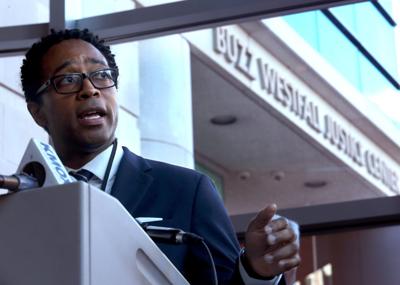

That is why new St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Wesley Bell announced on his first day in office that St. Louis County of child support in most cases.

People are also reading…

The move puts Bell squarely in line with a national criminal justice reform trend, which is evident in many recent moves by courts, prosecutors and lawmakers to decriminalize what are more often than not crimes of poverty.

Just a few days before Bell’s dramatic shift in policy, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northum, a Democrat like Bell, announced a plan in his state for failure to pay court costs, including in child support cases. That move follows a federal court decision in Tennessee that ended that state’s policy of suspending driver’s licenses for folks who can’t afford ever-increasing court fees and fines.

The logic behind such reversals of long-standing practices is simple: How can somebody pay child support if they’re in jail? How can a defendant get a job to pay court costs if he or she can’t drive to work?

Those moves, though, point to an ongoing challenge Bell will face, even in seeking civil enforcement of child support cases. When the criminal justice system focuses primarily on punishment — and financial incentives — sometimes the results aren’t very just at all.

Jason Sharp knows that all too well.

Nearly seven years ago, Sharp was $350 behind in child support. He was charged with a misdemeanor in Caldwell County. Associate Circuit Judge Jason Kanoy issued a warrant for his arrest. Sharp was picked up after being stopped for an alleged traffic violation. He spent more than 30 days in jail, unable to afford bail.

He pleaded guilty to nonsupport and was given time served. But he also was required by Kanoy to serve two years on probation, supervised by a private probation company, which is standard in many parts of rural Missouri.

A couple of months into the probation, the prosecutor says, Sharp violated probation, partly because he hadn’t paid the costs foisted upon him by the private, for-profit company, as well as the $1,575 bill he received from the county for his stay in jail. Also, Sharp hadn’t found a job.

“I was trying to find a job,” Sharp told me. “But the whole time you’re paying these costs, you have to go to court every month.”

Sharp got caught up on his child support.

But to this day he still owes on his jail bill.

Twice since he paid his back child support and served his time, he’s been arrested for failure to pay his jail bill and served more time behind bars and received a higher bill. His probation has been extended.

He’s still tethered to Kanoy’s court.

Sharp’s next court date is Feb. 7. That’s one day after the Missouri Supreme Court is scheduled to hear arguments in , in which the Missouri State Public Defender’s office, the American Civil Liberties Union and Attorney General Eric Schmitt are all arguing that the practice common in Kanoy’s court — and many other courts in Missouri — is illegal. There’s nothing in state law, they say, that allows judges to haul defendants into court month after month, for years, with the threat of criminal contempt, for failure to pay jail bills.

That issue isn’t a problem in St. Louis County, which doesn’t charge people for stays in jail.

But it is a thread in the same criminal justice tapestry that caused Bell to decriminalize the failure to pay child support.

For Lummus, the issue is simple.

“When I can get somebody who wasn’t paying, to pay what they can afford, they not only pay, they are proud to pay,” she says.

On two fronts, that’s the story of criminal justice in Missouri these days.

In St. Louis County, Bell wants dads to be able to get the sorts of jobs that will improve their ability to actually make their child support payments. Meanwhile, the Missouri Supreme Court soon will decide if a similar philosophy should be applied to poor people in rural counties, where too many judges use jail debt as a government-approved ball and chain.