Carlos Johnson called from county lockup.

He wasn’t in a good mood.

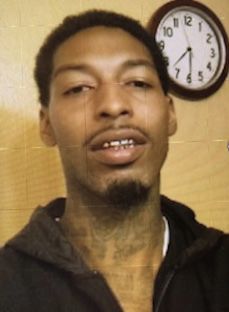

Carlos Johnson. Photo provided by Johnson family.

“I am still being punished for something I didn’t do,” Johnson said.

In jail, that’s not an uncommon sentiment. In jail, everybody’s got a story.

Johnson’s is a damning tale about the left hand of Lady Justice not knowing what the right hand is doing.

Last week, a St. Louis County jury found Johnson not guilty of three serious charges. The 36-year-old Ferguson man — he grew up in Kinloch — had been charged in 2015 with the fatal shooting of Calvin Sharp of St. Charles. Johnson was charged with second-degree murder, armed criminal action and being a felon in possession of a gun.

People are also reading…

About the only thing the St. Louis County prosecuting attorney’s office got right is the felon part.

Johnson has been in and out of jail and prison for much of his adult life. He has gun and drug convictions, and one for attempted armed robbery.

But this one, he says, his public defender says, and a jury agreed after a trial, he didn’t do.

“I knew I wasn’t guilty,” Johnson told me. “I know my truth.”

His current truth is this: Johnson is still in jail because a judge in the city found him guilty of the crime he was accused of in the county before he ever went to trial.

In February, Johnson had a probation violation hearing before St. Louis Circuit Court Judge Steven Ohmer. The hearing was a result of his murder charge in the county. At the time he was charged, Johnson was on probation in the city for a 2015 conviction of being a felon in possession of a gun. The private company overseeing his probation in the city — Eastern Missouri Alternative Sentencing Services, or EMAS — filed a notice with the court alleging a violation of the probation condition that Johnson not violate any laws.

At the hearing before Ohmer in the city, the prosecutor in the county case, Kimberly Kilgore, testified against Johnson, something that Johnson’s county public defender says is unheard of. Johnson’s city public defender, Ryan Hehner, objected to Kilgore’s testimony but was overruled. Then, before Ohmer ruled on the probation violation, both Hehner and Johnson made a reasonable request.

������Ƶ were going to win the case against Johnson in the county, they told Ohmer. He was innocent. Why not delay a ruling in the probation violation case? It wasn’t like Johnson was going to get out of jail before his murder trial.

“I was just hoping that you would give me the chance to — for my trial to play out,” Johnson told Ohmer at his probation hearing.

Ohmer declined. “You can have your day in court,” he told Johnson, “but I am not convinced and I’m not comfortable with someone on probation to me and these kind of things going on.”

Ohmer sentenced Johnson to 15 years for a probation violation.

A year and four months later, a St. Louis County jury determined that the basis of that violation no longer exists. Johnson didn’t, in fact, break the law. He had no gun. He committed no crime. So said the jury.

Johnson’s public defender in the murder case, Megan Beesley, calls the fact that Johnson is still in jail a miscarriage of justice.

“This case is a perfect example of someone who is actually innocent who has no way to prevent his own (probation) revocation,” Beesley says. “No prosecutor should ever be a witness in a probation violation hearing, because they are not neutral fact witnesses, and all they can testify to is hearsay that they learned from police officers. The other great unfairness that this case shows is the pressure that prosecutors can use to force innocent people to plead guilty. By revoking his probation, Ms. Kilgore put significant pressure on Carlos to take concurrent time on the murder. Thankfully, Carlos is brave and stood up for himself and fought, but Ms. Kilgore repeatedly offered concurrent time and complained to his murder trial judge that he wouldn’t take it.”

In Missouri, more inmates are in prison on probation or parole violations than actual criminal charges. More than 54% of the state’s prison population is there because of probation or parole violations, a greater percentage than all but two other states.

Johnson will soon be one of them. He expects to be transferred to the Department of Corrections any day, to serve a 15-year sentence for an underlying crime that a jury of his peers says he didn’t commit.

Probation cases, Beesley says, are far too often handled in a way in which defendants have little recourse when mistakes are made.

“There is no ability to appeal in that situation, and the judges are given too much latitude on probation cases,” Beesley says. “The justice system in the city completely failed him.”

She and Johnson hope Ohmer recognizes the injustice in the situation and reverses his ruling in the probation violation case.

“I hope he reconsiders,” Johnson says. “I hope he sees the light.”