When St. Louis and St. Louis County residents went to the polls this month, they took the latest step in a long trend around here:

The steady rise of sales taxes.

The “Arch tax,” as it is known, will add a sliver of a cent to each dollar spent on meals and clothes, furniture and electronics, starting Oct. 1. Three-sixteenths of a penny doesn’t sound like much, but the vote is one of many small decisions that have people here now paying some of the highest sales taxes in the United States.

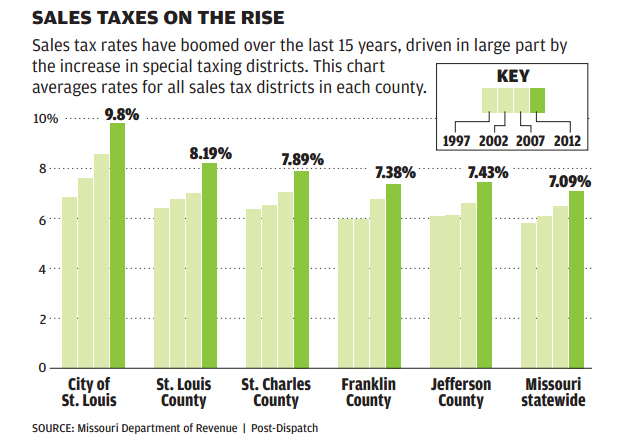

While rates vary across the region — by county, by city, by shopping plaza, sometimes even by building — the trend everywhere is up. The average sales tax rate in St. Louis County is now 8.2 percent, headed to 8.4 percent when the Arch tax starts. That’s up two full points from the 6.4 percent rate in 1997. The growth has been even faster in the city of St. Louis, where tax on a cup of coffee or a meal out can now run as high as 12 percent, after the city’s 1.5 percent restaurant tax.

People are also reading…

This has come despite growing anti-tax sentiment in Missouri, where state and local laws often require a public vote for tax increases and severely limit government’s ability to raise property taxes. Meanwhile, Jefferson City lawmakers talk far more about cutting income taxes than increasing them.

So sales tax, small and little-noticed at the end of a receipt, has become a go-to source for local governments that need to raise money.

“It’s not necessarily popular but it is easier than the others,” said Robert Cropf, a professor of public policy at St. Louis University. “When rates go up for (income and property) taxes, it’s much more obvious to taxpayers. Sales tax, literally, is nickel-and-diming people.”

That was part of the pitch for the Arch tax.

Supporters pointed out that the levy would add just two cents to a $10 purchase, while generating $780 million over 20 years for parks and bike trails and the Gateway Arch renovations. That kind of targeted appeal has helped win campaigns in recent years for countywide sales taxes for Metro, for children’s services and for emergency communications equipment. The region has a bevy of specific municipal sales taxes, too, that fund everything from work on streets to economic development incentives.

Voters are choosing to buy public services bit by bit, said Mark Tranel, director of the Public Policy Research Center at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

“It’s the accumulation of a rate over time,” he said. “A half-point here, a quarter-point there.”

It adds up.

RISE OF TAXING DISTRICTS

Today, sales tax rates here — combined state, county and local — are some of the highest in the country. A study last year by the Tax Foundation tallied the nation’s 108 biggest cities by sales tax rate and found St. Louis’ 8.49 percent base ranked 25th, with half the cities ranked higher located in states that don’t have income taxes. Many St. Louis County municipalities aren’t far behind.

And that study didn’t count another factor that has driven taxes even higher in a growing number of places here.

The use of special taxing districts — community improvement districts and transportation development districts — has exploded in recent years. These privately run entities levy an extra tax to fund anything from work on streets to security details, and have become an increasingly popular piece of financing for developments large and small. There were seven in the region in 2001, according to data from the East-West Gateway Council of Governments. Today there are about 200, covering everything from the Ameristar Casino in St. Charles to the St. Louis restaurant strip known as the Grove.

Nineteen of these districts — including Macy’s and the MX building in downtown St. Louis, the newly rehabbed Cheshire Inn on Clayton Road, and much of the Delmar Loop — are both a CID and a TDD, which boosts sales tax by 2 percentage points.

The districts are typically created by owners of the buildings in them, but need the approval of local elected officials. Most see them as a no-lose proposition.

Not long ago, the St. Louis Airport Marriott in Edmundson had mold so bad that some of the rooms couldn’t be used, said Mayor John Gwaltney. Town officials wanted to see the hotel — one of its biggest taxpayers — returned to its “glory days,” Gwaltney said, so they approved a CID and TDD to help raise money for a renovation. Now the place carries the highest sales tax rate in the St. Louis area: 10.7 percent, not including a hotel-motel tax that tops 7 percent.

Gwaltney didn’t realize his town’s hotel bore that distinction, but he doubts the people who stay there realize it either.

“I don’t think it’s enough to matter much to them,” he said. “When people are making reservations, they don’t take into consideration how much taxes go into it.”

Besides, he said, the alternative was untenable. If the Marriott closed, Edmundson would have to cut services to its 800 residents, with free trash pickup likely to go first.

“It would have been devastating to us,” Gwaltney said. “It’s one of our major revenues.”

As at the airport Marriott, most of the people who eat and buy gas along McNutt Road in Herculaneum come from out of town. To city administrator Jim Kasten, that made the area around an off-ramp from Interstate 55 a logical place for a TDD to fund some needed roadwork. Now a 1-point higher sales tax at a Cracker Barrel, Dairy Queen, hotels and gas stations is helping fund the $12 million project.

“My people, Herculaneum people, are not paying the bulk of that,” he said. “People driving the highway are paying the load.”

After all, it’s often those drivers who use the street improvements. Charging them only makes sense, said Brentwood Mayor Pat Kelly, whose town joined with Maplewood and St. Louis County to build several road connections around the busy corner of Hanley and Eager roads, paid for with a 1-cent sales tax at the many shopping plazas there.

“Why would we want to assess a property tax against our residents?” he said. “TDDs are set up for these types of projects.”

And it’s not affecting business; bustling Brentwood keeps producing more sales tax revenue.

“Our stores seem to be doing well,” Kelly said. “When stores leave, we’re able to fill them.”

TIPPING POINT

For their part, shoppers often barely notice, whether in low-tax areas like the South County Mall, where the sales tax is 6.9 percent, or the Del Taco-turned-Starbucks on South Grand Boulevard in midtown St. Louis, where the rate is 12 percent, including the 1.5 percent restaurant tax.

“Things did seem a little high on the ticket,” said Antrianna Evans, 19, a student at St. Louis Community College, recalling her last trip to the Starbucks. “It was expensive for a hot cocoa.”

Still, Evans said, the sales tax won’t keep her from coming back. “It’s in a nice area. It’s big and comfortable. They have free WiFi,” she said. “They know they’re going to make their money.”

Across town, at a Starbucks in Webster Groves, Kate Story said much the same.

“I don’t really think about sales tax that much,” the Webster University student said, while drinking a black iced tea on which she’d paid 8.4 percent sales tax. “Unless it’s in regard to cigarettes. And that’s another whole ballpark.”

Still, there likely are limits to this, said Phyllis Young, a St. Louis alderman whose downtown ward includes a number of CIDs and TDDs. She generally supports the districts — they’ve helped pay for important rehab projects such as Lafayette Square’s City Hospital, the Railway Exchange Building on Olive Street and the Hilton St. Louis at the Ballpark — but she also understands the worries about ever-rising rates.

“We can’t continue to use sales tax as a basis for financing the city’s needs,” she said. “We’re already at the high edge of that.”

Moreover, many say sales taxes place a heavy burden on the poor, who spend more of their income on everyday needs, like clothes and household needs.

And yet it could soon get even higher. The Legislature is considering two proposals this spring that would hike Missouri’s 4.225 percent state sales tax rate.

One would create a 1-cent tax on purchases statewide to raise $8 billion over 10 years for highway projects. It’s moving through the Legislature, and if it passes there will get a public vote. Lawmakers are also mulling a plan to cut income taxes and make up some of the lost revenue by hiking the state’s sales tax by another half-point.

Here in the St. Louis region, many experts say billionaire investor Rex Sinquefield’s push to end the city’s earnings tax will likely lead to higher sales taxes. And sales taxes are a common tool to help fund sports stadiums, which could be an issue here, should regional officials agree to help pay for a new or improved home for the St. Louis Rams.

It’s not entirely clear how much more appetite St. Louisans have for higher sales taxes. Eventually, says Tranel, the region could reach a tipping point and sales tax hikes will become as hard a sale as income tax hikes are now. But that hasn’t happened yet.